Léonie Sonning Prize 1998

The German soprano Hildegard Behrens received the Léonie Sonning Music Prize of 300,000 Danish kroner at a concert on 6 June 1998 at the Tivoli Concert Hall. The concert was broadcast live on the Danish Broadcasting Corporation’s P2 radio channel.

The prize was presented by the Royal Theatre Kapellmeister Poul Jørgensen, chair of the Léonie Sonning Music Foundation’s board, who in his speech remarked:

‘Seldom is an artist so able to reconcile theatrical expression with the musical intentions of the composer. With your beautiful and expressive voice, your enormous strength and willpower, and your compulsion to avoid compromise, you have delivered rich, nuanced interpretations of your chosen roles with a presence that is extraordinary.’

Motivation

The Léonie Sonning Music Prize 1998 is awarded to Hildegard Behrens in recognition of her artistically nuanced and multifaceted interpretations of the opera literature’s dramatic soprano roles, new and old. With her powerful and sonorous voice, theatrical intensity and stage presence, palpable charisma and authority, Behrens has been a fixture in opera houses around the world and a barometer of her generation’s understanding and interpretation of some of opera’s most vocally, musically and dramatically demanding roles.’

The programme

Wagner Siegfried’s Journey down the Rhine, from Götterdämmerung

Wagner Final Scene from Götterdämmerung

Richard Strauss Macbeth

Richard Strauss Final Scene from Salome

Richard Strauss Zueignung (encore)

Participants

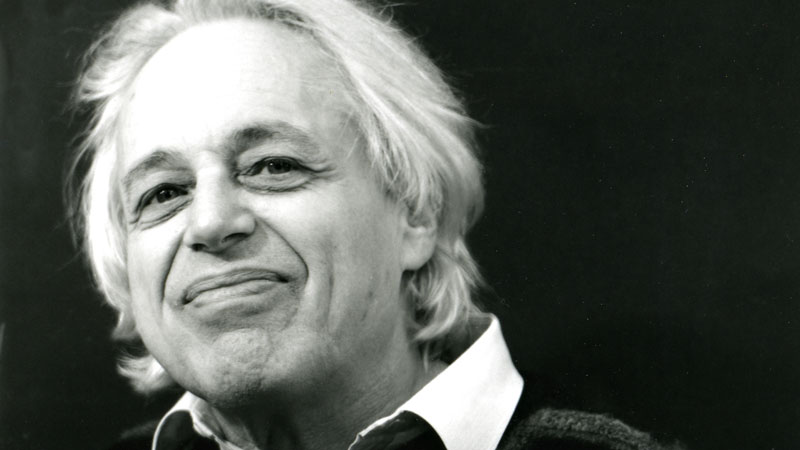

Hildegard Behrens, soprano

Tivoli Symphony Orchestra (Copenhagen Phil)

Michael Schønwandt, conductor

The Daily Press wrote among other things:

Behrens has turned 60 and is admittedly at the end of her career. Make no mistake, she still has plenty to give even if her voice may not be what it was, including a full-bodied core sound delivered straight and an admirable fervour of expression. Nor has her stage presence diminished over the years. So her receipt of the award was well justified, first with the finals scene from Götterdämmerung and then that from Salome. It was marvelous to see a humble, flattered, almost shy but very happy Behrens express thanks for the award and in the next moment see her as a dramatically alluring and sensual Salome – and indeed a proud Brünnhilde with juice and fullness in her voice. It was her uncompromising, intense and multifaceted interpretations of the opera literature’s dramatic soprano roles that were highlighted in the Kapellmeister Poul Jørgensen’s speech – interpretations that border on what is humanly possible. Big words, but well-deserved in Behrens’ case, and it is gratifying to note that her acting abilities were also significant in her winning of the prize.

(Jakob Wivel, Jyllands-Posten, 1 June 1998)

The 61-year-old has gleaming firmness and penetrating sustainability in full: an overwhelmingly sparkling top register, a metallic depth that is almost unique and unrestricted agility. She can soar through a phrase so that the listener is pinned back in their seat, while also mastering the most delicate intimacy with inner luminosity. We were given plenteous examples of both. And then she has the charisma to go deep in to her characterization. Towering in a black dress, the widow Brünnhilde stepped forward and filled the stage with mature decisiveness. The voice flushed through a room already filled with the orchestra’s tidal wave of sound, and the face shone in explanation. Then she sang of her love for Siegfried. The sound was muted. Warmth and tenderness shone through, the heroine assumed human dimensions and continued to confide her dawning understanding of the implications of the situation for those closest to her (actually to her physically absent father, Wotan). At the meeting with her horse Grane, a glimmer of joy flared up before she rode into her husband’s funeral pyre. When she returned as Salome, a flaming red shawl was added to the costume. Now the passions flowed into a study of voluptuous, abandoned triumph and bittersweet frustration. If the voice was whiter and hotter than in the first furious outburst, next came the whole vocal response to Strauss’s elaborate orchestral drama: the potent mixture of cruel mockery and nagging longing for John the Baptist’s severed head and an eerily trembling tenderness in the memory or imagination of what he was.

(Jan Jacoby, Politiken, 8 June 1998)